The reciprocity of the wood wide web with merlin sheldrake

“Because we could not do

what we do unless

they did what they did.”

Merlin Sheldrake is an acclaimed biologist and author diving deep into the fascinating world of mushrooms and fungi. Known for his groundbreaking research on the symbiotic relationships within the "wood wide web," Merlin sheds light on the interconnectedness of forests and the vital role fungi play in ecosystem health.

Merlin spoke with Lily Cole - exploring symbiotic puzzles, fungal secrets, and nature’s fundamental reciprocity. You can listen to more of their conversation via the Who Cares Wins podcast.

LC: What fuels your fascination with fungi?

MS: Fungi are the great recyclers, the great decomposers of the planet. And if they didn't do the work of decomposition, then the surface of the earth would be piled kilometres deep with the bodies of animals and plants.

So we live and breathe in the space that fungi leave behind. That's something quite hard to take on board because what they’ve left behind is negative space. This is a thought that always struck me as a child. I couldn't get my head around this: that we live in the space that they leave.

There are so many other things that fuel my fascination with fungi. One is the astonishing ability of fungi to form symbiotic relationships that have long shaped the history of life, and which underpin our own lives on this planet. Like plants, for example, which are the outcome of a symbiotic relationship between algae and fungi.

Almost all plants depend on fungi, which live in their roots and harvest minerals and water from the soil and trade them with their plant partners. And in return the plant provides the fungus with sugars and other energy containing compounds that it produces in photosynthesis. So when we eat plants and we touch plants, when we walk around in an environment filled with plants, then we are walking around an environment filled with the outcomes of symbiotic relationships.

I was quite interested to discover that a large part of Darwin’s work looks at the role of cooperation in evolution. That struck me reading your book as well. It seems to me cooperation and symbiosis are instrumental parts of how you understand the natural world to work. Would that be fair to say?

Yes. I think that's fair to say. Competition and conflict are certainly important, but so is cooperation. We ourselves are the outcome of intimate cooperation between many different organisms: We have more bacterial cells in and on our bodies than our own cells.

Besides, each of our cells has mitochondria inside, which were once free living bacteria. So even our cells arise from intimate associations between otherwise unrelated organisms.

To think about one without the other is to skew the picture. So the way I like to think about it is that life is a process of collaboration, and collaboration itself is an alloy of competition and cooperation. This is an idea that we're familiar with: You know, you can have a functioning family unit and you can have competition and cooperation playing out in that family at the same time. Or a touring band that cooperate enough to give an astonishing performance on stage, and at the same time they can quarrel backstage and on the tour bus

So these dynamics can coexist. I think it's best to step into a larger room where cooperation and competition can both take place and both be key forces in how life unfolds.

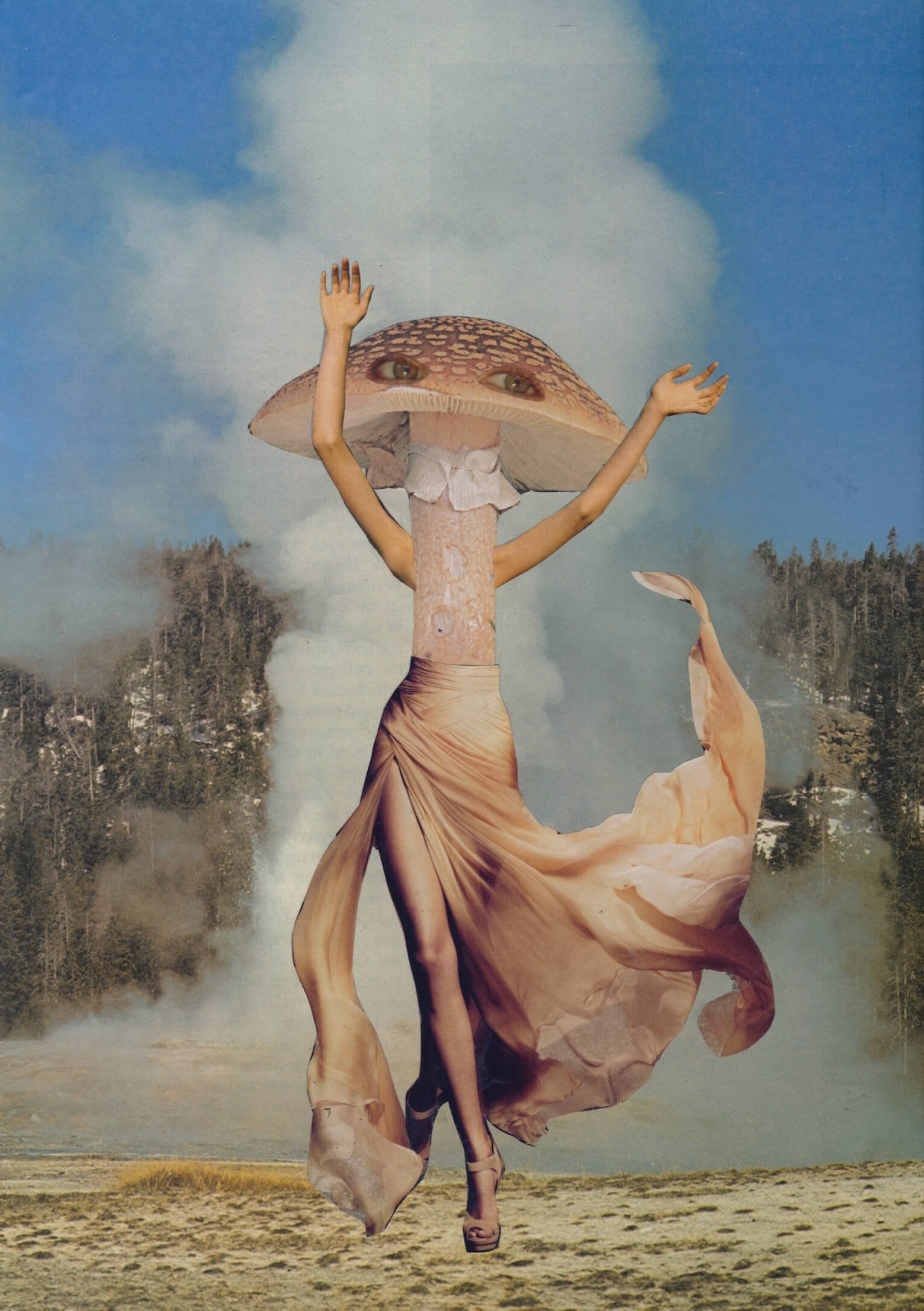

Under A Spell by Seana Gavin

I wanted to ask you about the example of the flower in Panama and its relationship to fungi in the soil.

Yes! So I was studying this plant called Voyria, which is in the Gentian family. It has bright blue flowers and thin, white stalks with no leaves. It doesn't need leaves because it doesn't photosynthesize. Instead, it acquires everything it needs to grow from the fungi that it forms relationships with underground. But these fungi themselves need to acquire their energy from other green plants. And so the fungi connect Voyria to nearby green plants. This means that nutrients are moving from the green plant through the fungus into Voyria. It’s a way of life that has opened up new biological possibilities. The plants that behave in this way have become gateway organisms to the idea of the Wood Wide Web as it's sometimes called.

Can you explain the wood wide web please?

Most plants depend on mycorrhizal fungi that live in and around their roots. And these mycorrhizal fungi depend on their plant partners. The plants provide them with energy. The fungus provides the plant with other nutrients. But the plants are promiscuous and they can plug into more than one fungal network. And the fungi are promiscuous and can engage with more than one plant.

And the outcome is shared overlapping networks of plants coupled by fungi, or you might say fungi coupled together by plants. And in some cases, as with Voyria, nutrients can move between plants through these networks. Although in other cases, the networks can amplify the competition between plants. And in some cases they might not have much effect at all.

Do you argue that the fungi are also communicating through the plant?

I think you can see it both ways, yes. Most of the research into this has taken place in a plant centric way, seeing the plants as the nodes in the network and the fungi as the links. It's as if the fungi are the cables linking together the routers make up the internet. But it's not really fair on the fungi because fungi are organisms with a life of their own. I find it helpful to flip the perspective.

I like that resistance to an anthropocentric worldview. With the example of the Panama Flower, just to clarify: So the flower is getting nutrients through the fungi because it can't photosynthesise. What do you imagine the fungi get out of that relationship?

So this is an open question. Right now it's commonly assumed that the flowers are parasitic on the fungus because they don't appear to give anything back. Because they don't have anything to give back. At least not in the nutrient currencies that are commonly studied.

The assumption is that if they don't have anything to give back, then they must just be taking without giving anything back. However, to show that they were parasites, you'd have to demonstrate that they were having a negative effect on the fungus and that's really hard to do with the experimental techniques available to us right now. So this hasn't been demonstrated and so there might be other ways that the plant might be helping the fungus. For example by providing a shelter in its roots from the hustle and bustle of the soil. It's possible that the plants could allow the fungus to synthesise certain minerals or vitamins. We're not sure.

Anthropologists argue that this is probably the oldest way that human societies have worked together: through reciprocal relationships of giving and receiving. It makes sense to me that you can't give without receiving - you give in part because you receive and you receive because you give, -they are intricately connected. And that seems to be playing out in nature all the time in these symbiotic relationships.

Yes, many of them are reciprocal, intimate, mutual dependencies and frequently illustrate that organisms or humans can accomplish things together that they couldn't accomplish by themselves. The key to this process is that one is providing some kind of service or can achieve an outcome that the other one is not able to do and vice versa. And together those abilities become a super ability that can happen only when they’re together. So you can see that as a kind of gift if you like, because if one organism is overproducing something, then the other organism can depend on that and in return it can overproduce something which the other one can then grow to depend on.

LIFE IS SYMBIOSIS ALL THE WAY DOWN.

I love that. It makes me think about remodelling the way we understand our relation to one another in human society. In the bigger picture I also think it has the capacity to make us rethink about our relationship with other organisms and other species and move away from an anthropocentric worldview that quite often sees humans as very separate from nature. And it reestablishes the fact that we are an integral part of nature and in order to receive from nature, we also need to give back to it.

I think it's so important to reevaluate what we think about as ourselves. Because we tend to think of ourselves as the very neatly bounded individuals acting in our own interests. Capitalism depends on individuals acting in their own interests, making supposedly rational decisions. But actually on a biological level it's not so easy to work out where these boundaries between individuals can be drawn. After all, as we know, as we’ve discussed, we carry around more microbes than our own cells and all organisms have symbiotic relationships without which they couldn’t do what they do.

Big bacteria can have small bacteria living inside them, and big viruses can have small viruses living inside them. Life is symbiosis all the way down. And if this is the case, if the boundaries between organisms are not as clear as we like to think: what counts as an individual becomes a question rather than an answer known in advance.

If we think about the limits of ourselves as somehow porous, then it's harder to draw an unbreachable boundary between us and the rest of the living world. And without that unbreachable boundary between us and the living world, it's harder to justify environmental exploitation or any of the difficult and damaging behaviours that we pursue so eagerly today.

Learn more about Merlin’s work on merlinsheldrake.com or listen to more of his conversation with Lily Cole via the Who Cares Wins podcast episode.

Fairyville by Seana Gavin

Mindful Mushroom by Seana Gavin

Seana Gavin is a London based artist working primarily in the medium of collage. She combines distinct images from vintage photographic material to create otherworldly scenes, transforming them into dreamlike environments where the past and future coexist. Drawing inspiration from traditional landscape painting, Heironymus Bosch, surrealism, Science Fiction, different states of consciousness and places she has visited in her life.

She uses printed materials as her ‘paint’ and building blocks to create totally unique images and compositions from her imagination, creating instantly recognisable artworks in her signature style of collage. Gavin is also known for her photographic work, documenting her time involved in the free party rave movement during the 1990s.

Gavin, a graduate of Camberwell College of Art, has had solo exhibitions at galeriepcp, Paris (2019), Celestine Eleven, London (2014) and the B Store on Savile Row, London (2011). Her work has been included in group exhibitions at major art galleries and institutions including The Nobel Prize Museum, Somerset House, Fundacao de Serralves, The Walker Art Gallery, the Wellcome Collection, The Saatchi Gallery and New York’s The Hole.

She has collaborated with brands such as Farfetch, Miharayasuhiro, Kilometre Paris, La Prairie and Bodyshop. Her work has been included in publications such as Elephant Magazine, Financial Times HTSI, Twin, Wonderland, Dazed & Confused, Sleek, Vanity Fair France, and online at NY Times, i-D, The Face, 032c, Frieze and Anothermag. Gavin’s artwork features in the permanent collection of the Soho House Group on display at their clubs in London, Amsterdam, Miami and Chicago. A profile of her work has been included in The Age of Collage 3, published by Gestalten (2020). She also published a photography monograph Spiralled with IDEA books in 2020, which was selected as ‘Work of the Week’ by Art Review.

What message do you aim to spread with your artwork?

My intention is for my art to make the viewer feel as if they are entering a physical space or an imaginary world. I want my artwork to be very accessible to everyone. You don't need to read a dissertation to understand it; it's more immediate. People will have an instant reaction when seeing my work; they will either connect to it aesthetically or they won’t. I’m hoping it will make the majority smile.

How did your journey with portraying mushrooms start?

At the core of my collage work, I am creating otherworldly environments and landscapes. I am interested in different states of consciousness where the rules of reality are not relevant. I’m also inspired by ideas of life on other planets as well as thoughts of future worlds. So, mushrooms often become part of those environments.

I have always associated mushrooms and fungi with fantasy environments from childhood fairy tales like ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and old Science Fiction films. They definitely have a very alien look to them. I spent my childhood in Woodstock, upstate New York. There is a history of creatives living there and also a strong connection to DIY culture. Many people we knew there bought land and built their own houses. A friend of mine lived in a house that looked like a giant puffball mushroom with windows. I think this is what inspired the mushroom architecture themes that sometimes pop up in my work.

Mushrooms have appeared in my work since day one. I have always found them incredible. I have always been fascinated by them for their endless variety of colours and textures. The more I studied them, I started to see them like people with different personalities, shapes, and skin tones. So, I started an ongoing series of mushroom portraits, with facial features and arms. More than anything, I just find them really fun to make! I think people connect to them because subconsciously they are attracted to the familiarity of something that looks human.

What have mushrooms taught you about being an artist?

I'm sure it is no surprise to say I did experiment with mushrooms and psychedelics in my youth, though I didn’t have the best experience with that, as I always had bad trips. But I am grateful for how they may have opened up my imagination.

What do you enjoy most about working with collages, and how do you think art can help us connect with nature?

I fell into collage randomly and it was very instantaneous. I studied drawing at Camberwell but didn’t make any work for 10 years after leaving Art school. I became creatively blocked. It was my sister who suggested I attempt collage. I immediately enjoyed it and loved the fact I could play around with imagery on a page without the daunting feeling of a blank canvas. Collage brought back the fun of making work again, without overthinking or analysing. It allowed the natural flow of expression and creativity.

I work intuitively and organically, in the same way that plants and flowers in nature grow. I allow things to flow in the same way when I am creating a piece. So in that sense, it connects to nature. But really, I would say it is nature that helps me to connect to art. As I am also inspired by the botanical and natural world, and often include places that I’m lucky to visit in my life and travels into my artwork.

To learn more about Seana's work, we invite you to visit her website: seanagavin.com